Talking about Covid-19 among Latino asylum seekers and refugees.

Have you ever seen an alien? A real alien? Despite the pervasive use of this term to picture foreigners, I guess the answer is no. Are witches real? Of course not! Not unless you visit a museum or thematic park. It seems nobody has ever seen an alien or captured a witch. Yet, references to alien invasions and witches are growing unceasingly during this period of Covid lockdown, as indeed are many other conspiracy theories.

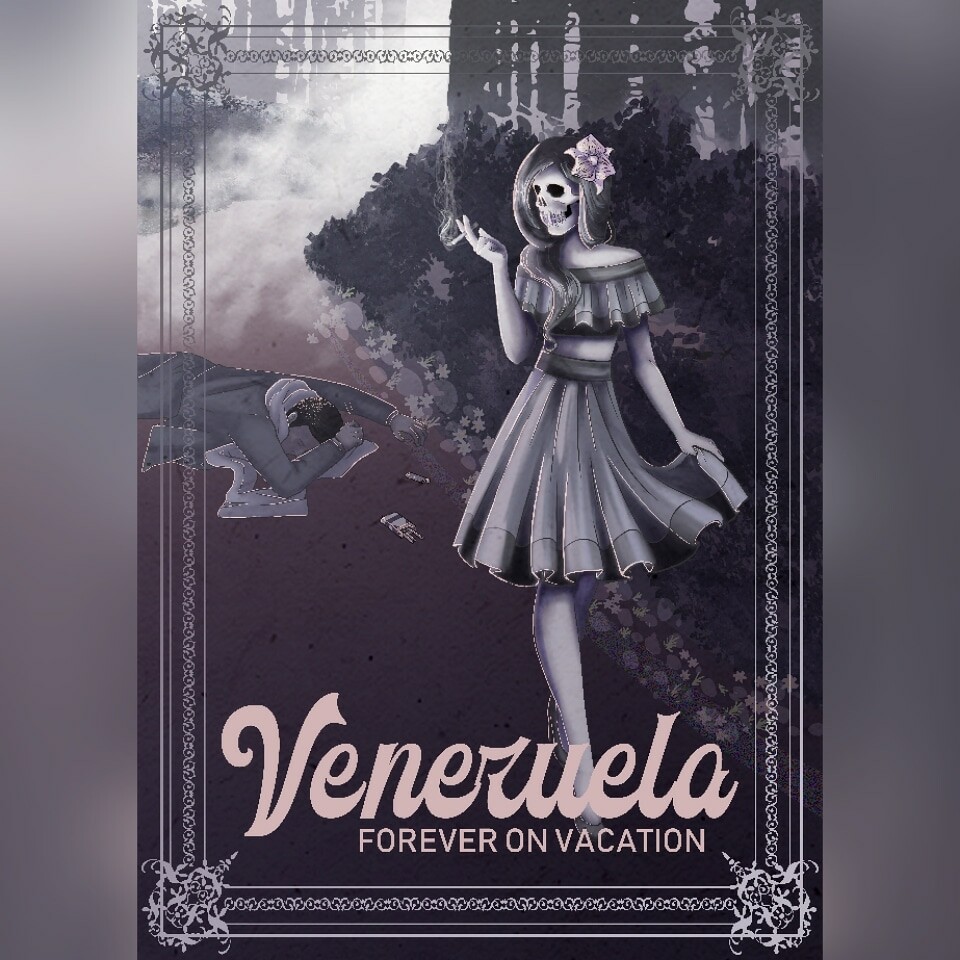

The instinct to believe is deeply human, especially to believe in higher powers. Maslow gave us a cue to understanding our incurable credulity but he wasn’t thinking about Latino magic realism. He had no idea about the blood sucking monster Chupacabras, the vengeful spirit Sayona (image below), the mythical ghost monster El Coco that permeate our folklore or our good will politicians. Their common refrain during the pandemic is “we are here to serve” but we fear that they serve their political interests over the people’s. None of the populist leaders who are in denial about the dangers of the pandemic or who acted too slowly are in captivity but, like aliens witches and monsters, they have legions of faithful believers.

Strange things happen every time we talk about COVID19 among asylum seekers and refugees from Latino backgrounds. Aliens and witches are constantly being invoked. The old axiom “We are what we think” doesn’t seem to sit well with what seem to be common attitudes toward this pandemic.

Since March, as part of my research for our Cov19Chronicles project, I’ve been having long conversations with friends and acquaintances belonging to three Central American and South American diasporas. The idea was to gather chronicles about their experiences of these uncertain times. A pattern emerged and a clear picture began to take shape:

Are you fearful about the virus?” I’d ask.

“No, not really, not yet”, was the common reply.

“How are you doing during quarantine?”

“Fine, all is fine, like normal really- not much to worry about”

“Seriously?” I’d ask.

“What do you think about the Covid virus?

“Hmm… looks like the virus is a try-out to control people.

“Nobody has seen the bat” (The original Chinese bat who supposedly brought the Covid to humans)

This last question elicited some responses that proved to be very revealing:

“Have you taken protective measures against the Covid virus?

“Absolutely! We try to maintain social distancing. We’ve got the best possible quality masks and gloves and we remain at home”.

I must to confess, I laughed secretly and forced myself to refrain from asking

“Why the hell do you doubt the dangers of Covid19 at the same time as you’re using masks?1?”

The many conversations that I have had bring to mind an old but wise Spanish proverb: “De que vuelan, vuelan” or “I don’t believe in witches, but if they fly, they fly.”

This proverb is well-known among us Latinos and is part of the way we were raised. It suggests “be ready just in case something happens”. You might say “forewarned is forearmed”.

Every migrant carries around with him or her their cultural luggage – and this includes the metaphors we live by. Sometimes these metaphors fit easily into their new lives in foreign countries, sometimes not. We are challenged not only by differences in ways of living, beliefs, languages, ethnicities, but also by the hopes and expectations we hold that can add up to feeling of being jinxed by aliens and witches – our imagination is one of magic realism.

Covid19 and its not so subtle consequences seem to jinx us as asylum seekers and refugees: exclusion, prejudice, poor access to essential services, ignorance about our rights, lack of self-awareness or battering our hopes of achieving our true potential, and in some cases rampant contemptuous attitudes towards our aspirations and dreams – seeing us as worthy only of pity or disdain.

For decades, I have been working with vulnerable communities, first in my native Venezuela and now in the UK. As a refugee myself who works to support migrants from diverse countries, I am convinced that, despite our differences, displaced people share a common dream: to be part of their new society by contributing to it. But we face a common obstacle: being treated as aliens, like a virus, only beneficiaries of the state, victims or villains. We are not permitted or we are not able to contribute our labour, skills and talents for the greater good in our new land. Instead, we must live on the margins, in the hope that one day we can become whole again and contribute wholly and fully to society – for mutual benefit. This is the mutual life we desire. Our mutual life is limited in the UK, due to restrictive laws that prevent us from exercising full human agency – working, contributing and living fully.

If reciprocity is the fundamental value that binds people and societies together then surely the give and take between migrants and hosts should be encouraged and valued? This could of course be an endless discussion but I would like to separate reality from magic. Inclusion alone is not enough to build a society together. We need to aim at real integration as a total achievable goal but this can only be done by joining forces, by mutuality, reciprocity, respect, opening opportunities for all to succeed by fighting social inequalities and giving everyone a fighting chance to succeed.

The virus is an alien force, as indeed we often feel ourselves to be in our new countries. The virus too appears like magic, like a witch, trying to control us. Our instinct is to resist to defend and protect ourselves. Resistance is in our political DNA in Latin America and in diaspora. We may feel laws and restrictions and viruses jinx us, disable us, preventing us from contributing, but continue to nurture our hopes of a full life.

Comments

Submit a Comment